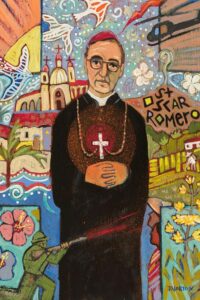

Born on 15 August 1917 in humble circumstances, which he never forgot, Romero was ordained priest in April 1942. For 25 years he served as a dedicated pastor and became a popular preacher. He was a surprisingly shy and self-effacing man who had a deep prayer life and was devoted to Our Lady Queen of Peace. He lived very simply and invariably responded with genuine compassion to the poor and needy. He was loved by his people.

When years later, in 1977, he became archbishop, his country was embroiled in social and political conflict. Great wealth came to the country’s landowners from coffee, sugar cane and cotton exports but for the landless peasants there was ever more desperate poverty and hunger. The rich were getting richer and the poor poorer. Every effort at change was rebuffed by massive electoral fraud and the violent repression of peaceful protest. From his cathedral pulpit Archbishop Romero became the voice of the voiceless poor. He made an ‘option for the poor’ – they were at the very centre of his concerns. His love of God and his love of the poor were inextricably entwined.

In his preaching and teaching he set out and explained Catholic Social Teaching, simply and eloquently. He then sought to make real in the lives of his people that challenging teaching of compassion, love, reconciliation and justice. He looked at the world from the point of view of the suffering poor communities and he tried to generate meaningful solidarity that would actually transform their lives. Every Sunday he spoke the horrible truth of what was happening in the countryside. With great courage he denounced the killings, the torture and the disappearances of campesino leaders; he sought justice and recompense for the atrocities committed by the army and police and he set up pastoral programmes to provide food, shelter and support for the victims of the violence. In advocating for their cause he gave them hope and encouragement.

With the emergence of armed guerrilla groups, civil war loomed. Archbishop Romero rejected the violence whether perpetrated by the left or the right. He strained every nerve to promote peaceful solutions to his nation’s crises, insisting to the wealthy classes that serious reforms were imperative. “It is only a caricature of love when we try to patch up with charity what is owed in justice, when we cover with an appearance of benevolence what we are failing in social justice” he said.

He was vilified in the press, his homilies were denounced as communist-inspired, missionary priests were expelled from the country, churches were occupied with tabernacles smashed and the Blessed Sacrament desecrated, six of his priests were assassinated and he himself received regular death threats – on one Sunday dynamite was placed behind the altar for his Mass but failed to go off. The atmosphere became so charged Archbishop Romero realised he was going to be killed. And he came to accept it. At 6.26pm on 24 March 1980, he was assassinated with a single marksman’s bullet.

He gave his life for his people. He died a martyr to the option for the poor, a martyr to the social teaching of the Church which he proclaimed and lived with absolute fidelity to his very last breath.

Every year on his Feast Day, 24 March, we will remember and celebrate his life and martyrdom. For us he is the model of a gospel-inspired teacher and practitioner, who seamlessly combined his deep prayer life with a courageous commitment to the poor. For the Romero Award, he guides us on our way as we strive to develop an authentic spirituality of justice and to become, in the words of Pope Francis, ‘a poor Church for the poor’.